“Back to School! Are you ready?”

Whether you are a student, teacher, parent, or an adult remembering your own schooldays as well as observing culture today, which sensations does the phrase “Back to School” and the question of readiness arouse in you? Butterflies of anticipation? Maybe even rising anxiety? If you’re a teacher, you’re probably wondering what your new students will be like; and if you’re a student, you’re similarly wondering what your teachers will be like. If you’re a parent or grandparent, you’re probably aware of the shape of your prayers for your children. And whether you’re a teacher, a student, administrator, parent, grandparent, or mentor, do you anticipate the new school year to be “easy” or “hard”? Do the new challenges cause anxiety or do you welcome them? And if you prefer “easy” over “hard,” why? (Is anyone voting for “hard”? I could be wrong, but I imagine not.)

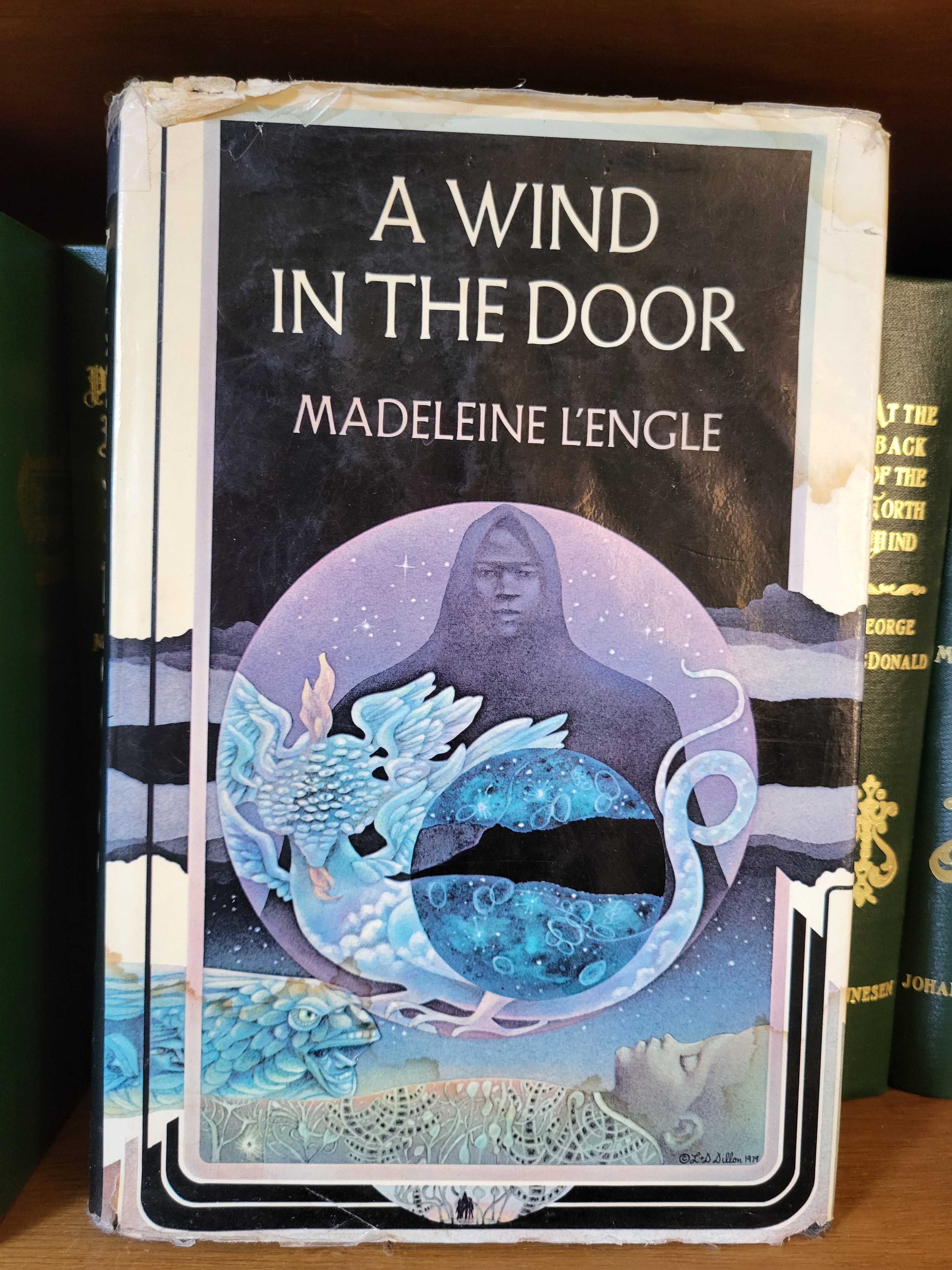

The question, “Why should school be easy?” in Madeleine L’Engle’s fantasy novel A Wind in the Door has stood out for me. When one of the main characters, Meg Murry, assumes that the Teacher, the angel Blajeny, has arrived solely to help her younger brother Charles Wallace with the problem of being bullied at school, Blajeny answers that this isn’t his problem.  Then he adds with a laugh, “My dears, you must not take yourselves so seriously. Why should school be easy for Charles Wallace?” Taken out of the context of the story, Blajeny’s response might seem uncaring, even cold, and possibly dangerous. But it’s clear in the story that this is not the case. The fact is that Blajeny cannot make Charles Wallace’s problem disappear. There is no magic wand. But Charles Wallace is learning to adapt and defend himself, and the once ineffective school principal Mr. Jenkins grows in moral character to the point where he looks forward to dealing with the problems in his schoolhouse. Unlike Meg’s small view of what this Teacher’s purpose is, Blajeny has arrived for the far greater reason of guiding his students into discovering the nature of their battle against evil, and therefore for strengthening their readiness to meet it.

Then he adds with a laugh, “My dears, you must not take yourselves so seriously. Why should school be easy for Charles Wallace?” Taken out of the context of the story, Blajeny’s response might seem uncaring, even cold, and possibly dangerous. But it’s clear in the story that this is not the case. The fact is that Blajeny cannot make Charles Wallace’s problem disappear. There is no magic wand. But Charles Wallace is learning to adapt and defend himself, and the once ineffective school principal Mr. Jenkins grows in moral character to the point where he looks forward to dealing with the problems in his schoolhouse. Unlike Meg’s small view of what this Teacher’s purpose is, Blajeny has arrived for the far greater reason of guiding his students into discovering the nature of their battle against evil, and therefore for strengthening their readiness to meet it.

Fighting a battle against evil is neither easy nor fair. Preparation for fighting the battles of life cannot be easy because the battles are not fair. And so proper schooling can never be easy. Wanting what looks easy could well mean taking ourselves too seriously in the selfish sense, or not seriously enough in the visionary sense.

Now that school or college and university has begun for many of us, I am left pondering Blajeny’s core challenge again: “Why should school be easy?” If I vote for “easy,” what am I looking for and, if I got it, would that be good? If I vote for “hard,” what should that be and why might that be better? Obviously, these questions can take us in several directions—the topic is that important. But for today I’d like to focus on Blajeny’s challenge: school should not be easy.

Now that school or college and university has begun for many of us, I am left pondering Blajeny’s core challenge again: “Why should school be easy?” If I vote for “easy,” what am I looking for and, if I got it, would that be good? If I vote for “hard,” what should that be and why might that be better? Obviously, these questions can take us in several directions—the topic is that important. But for today I’d like to focus on Blajeny’s challenge: school should not be easy.

If school should not be easy, and therefore should in some sense(s) be “hard,” how can we do this well? I shudder to think of needless pain that poor schooling can inflict on us, and I’m sure many of us can recall or know of damaging school stories. There’s much to be said about the topic of tender-hearted young souls eager to learn and flourish who then encounter cynicism, even cruelty, and begin to struggle with fear and anxiety. On a lighter note, but related, I recall the time when I taught a grade three creative writing class while I was teaching first year university English classes, and as I was thinking about the differences between my 8-year-olds and my 18-year-olds, I decided one day to ask my classes the same questions. Which students were eager? Which had the most inspiring answers? Yes, that’s right—the 8-year-olds. They were fresh and excited. They still believed they could learn. Around this time, I’d come across the curriculum thinker Dwayne E. Huebner’s book The Lure of the Transcendent in which he’d said (my paraphrase here) that the way schooling often happens has the effect of repressing the imagination of children by grade 5. It’s a sobering thought, one that we ought to wrestle with. And my experiment of asking the 8 and 18-year-olds the same questions seemed to affirm his point. Granted, other factors may have come into how my experiment worked out. Nonetheless, our task as educators, in every subject, is surely to inspire, to reawaken the imagination of all our students. Imagination, at core, is the ability to think otherwise and it involves the emotions. Another big topic.

This brings me back to my question, how can we do school that is “hard” and do it well? In life-giving ways? In the flurry of a new school year, in a world where the speed of change and often rising perplexities proliferate, where and how do we find our grounding? For me, words like excellence, freedom, and nurture readily come to mind.

First, excellence. Achieving excellence in any area is hard work. And in a culture where extensive leisure is deemed as the endgame, diligence isn’t terribly popular. Entitlement thinking comes into play too. “Things shouldn’t be so hard,” we might be tempted to say. And we’re all prone to sloth, especially laziness of mind. Thinking is hard work; it’s so much easier to trade in excellence for ease and conformity. Then distractions abound, pleasant and unpleasant. That “perfect time” in which to do something especially well hardly ever comes, or maybe never. Instead, we find ourselves striving for excellence against the wind, a fact that can certainly make us stronger if we persist. And we do it because excellence matters. Who wants a C+ surgeon, car mechanic, or performing artist? Products that malfunction and nobody knows how to fix? Mediocrity is everyone’s enemy just as excellence is everyone’s friend—or shall we say, true friend. School cannot be easy because life isn’t easy, and we need everyone’s skills applied wholeheartedly to rise to the challenges that fly our way. Excellence comes down to vocation, one’s calling in which we give back to the world the best that we have to give. Everyone is valuable; everyone is needed; everyone has a special part to play in the big drama of life. Who we are, who we become, and what we do matters.

Second, freedom. This likely isn’t the first word that we associate with a new school year. Perhaps these opposite words come to mind: ending, limitation, burdensome, even enslavement? In my blog “Summer Children” I wrote, “Summer can seem like a kingdom that should never end.” But freedom isn’t the same as leisure. Freedom, liberty of spirit, is fostered in the context of an education informed by moral wisdom. That takes work as well as courage. Historically, throughout Western thought, the highest purpose of education, broadly speaking, was to educate for virtue. To do this meant to cultivate strong critical thinkers: people who can think outside the box, who can innovate, who can discern error and point to truth. This came from a shared understanding that truth is an objective, unchanging standard. In the words of Jesus Christ, “the truth will set you free” (John 8:32). This quest for truth is the prerequisite to freedom. The question then becomes, how badly do we want truth? And freedom?

In his essay “Learning in War-time,” C. S. Lewis compares the educated person to the well-travelled one. He writes, “A man who has lived in many places is not likely to be deceived by the local errors of his native village: the scholar has lived in many times and is therefore in some degree immune from the great cataract of nonsense that pours from the press and the microphone of his own age.” Lewis, like others, was worried about the outcome of modern education based on moral relativism. Unlike the old idea of education founded on objective moral truth which is the basis for our freedom and intrinsic human worth, summed up nicely in the phrase “Veritas, Libertas, Humanitas”— Latin for “Truth, Liberty, Humanity”—a modern idea of education founded on moral relativism is the soil for enslavement and dehumanization. Lewis argues that moral relativism not only leads to inferior learning but opens the door to elite controllers who will work to reshape the masses to conform, and so enslave, to the agenda of their era. (See his book The Abolition of Man. Michael Ward’s commentary book After Humanity is a helpful guide here

In his essay “Learning in War-time,” C. S. Lewis compares the educated person to the well-travelled one. He writes, “A man who has lived in many places is not likely to be deceived by the local errors of his native village: the scholar has lived in many times and is therefore in some degree immune from the great cataract of nonsense that pours from the press and the microphone of his own age.” Lewis, like others, was worried about the outcome of modern education based on moral relativism. Unlike the old idea of education founded on objective moral truth which is the basis for our freedom and intrinsic human worth, summed up nicely in the phrase “Veritas, Libertas, Humanitas”— Latin for “Truth, Liberty, Humanity”—a modern idea of education founded on moral relativism is the soil for enslavement and dehumanization. Lewis argues that moral relativism not only leads to inferior learning but opens the door to elite controllers who will work to reshape the masses to conform, and so enslave, to the agenda of their era. (See his book The Abolition of Man. Michael Ward’s commentary book After Humanity is a helpful guide here .) Does this sound like an overly harsh judgment on much of modern education? Maybe, or maybe not?

.) Does this sound like an overly harsh judgment on much of modern education? Maybe, or maybe not?

Third, nurture. Who was your favourite teacher(s)? My favourite teachers and professors believed in us. They had high standards and they worked hard to help us reach them. They had a passion for their subject and its relevance. They believed we had a hope and a future. They did all these things in spite of our weaknesses and failures and in spite of the climate of the times. They cared about us. Yes, the very best teachers loved us. Can you really teach your students without love? I don’t think so, not if educating the whole person for life matters to us. The examples of our best educators continue to inspire, console, and strengthen us on our life’s journey. They passed on the baton so that we can run our race to the best of our ability—to do the things that God has placed us on this good earth to do.

The character Blajeny’s question in L’Engle’s A Wind in the Door, “Why should school be easy?” continues to challenge me. While I might opt for ease as a default response, I know that growth for myself and my students, intellectually and morally, means willingness for education to be harder rather than easier. Like Meg and the other protagonists in this novel, I continue to learn that we journey best in a community that honours excellence, freedom, and nurture, to name a few things.

Am I ready for school? Do I want it to be “easy” or “hard”? I’d say I want the ease of deep peace in the midst of much that can be and will be hard. And I want to agree to undergo what is hard for the sake of what is better, and ultimately best. Right now, at this new beginning, butterflies and all, I’ll just say, “I am here. I want to be present to my students and colleagues. And I do not journey alone.”

Thanks for reading, for listening!

You can order your copy of Letters to Annie at Amazon, FriesenPress, or through your local bookstore.

Sign up to receive my blogs at https://monikahilder.com/

Follow me on Social Media:

Watch for my winter blog in December: “A Guest on Planet Earth.”