It’s my privilege and my pleasure to teach some of my favorite authors like J.R.R. Tolkien to university students. More often than not they come to me as ardent Tolkien fans. Sometimes they wonder, “Was he sexist? Maybe racist?” and such questions make for much needed discussion. (Essentially, my position on these two important questions is “No. No.”) But not once have I met a student who doubted the author’s love of nature: of trees, trees, and of all green growing things. This celebration of the natural world, together with the indomitable courage of hobbits, elves, dwarves, and wizards against the forces of darkness, inspires hope. Middle-earth is worth fighting for. There’s something sacred at stake here.

It’s my privilege and my pleasure to teach some of my favorite authors like J.R.R. Tolkien to university students. More often than not they come to me as ardent Tolkien fans. Sometimes they wonder, “Was he sexist? Maybe racist?” and such questions make for much needed discussion. (Essentially, my position on these two important questions is “No. No.”) But not once have I met a student who doubted the author’s love of nature: of trees, trees, and of all green growing things. This celebration of the natural world, together with the indomitable courage of hobbits, elves, dwarves, and wizards against the forces of darkness, inspires hope. Middle-earth is worth fighting for. There’s something sacred at stake here.

While not overt, the sense of the sacred permeates Tolkien’s legendarium. Readers feel it in Gandalf, Galadriel, Tom Bombadil and Goldberry, in the very fields and woods themselves. When a reader had written to Tolkien, saying, “you … create a world in which some sort of faith seems to be everywhere without a visible source, like light from an invisible lamp,” Tolkien replied, “the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.” The Lord of the Rings, he explained, “is about God, and His sole right to divine honour.” This light then from an invisible lamp?—call it holiness. There’s a holiness that permeates Tolkien’s depiction of Middle-earth and beyond.

For instance, when Frodo in The Fellowship of the Ring experiences the loveliness of the elvish home Rivendell, the reader likewise feels that just being there is “a cure for weariness, fear, and sadness.” With the beautiful melodies and words of elven-tongues, we’re invited into this “enchantment” that to Frodo is like “an endless river of swelling gold and silver . . . flowing over him, too multitudinous for its pattern to be comprehended. . . .” Tolkien’s Middle-earth is a clear portal into such well-being, what we sometimes experience in our own lives and always long for. Here there is a holiness that heals. And just what does this holiness have to do with his celebration of the natural world? How to describe it?

In wrestling with this question, I point my students to the Incarnation—God becoming flesh in Christ—and speak to how this incarnational principle is at the core of all of creation, the very wellspring. At first, this rolls off my tongue as easily as reciting the Apostles’ Creed and praying the Lord’s Prayer. In speaking these words (reverently, I hope), I think I understand. Human beings are made in the image of God. Life is sacred. The natural world in its original creation and still visible today is holy, an embodiment of, a witness to, God’s character. As David writes in Psalm 19, “The heavens declare the glory of God, and the sky above proclaims his handiwork. Day to day pours out speech, and night to night reveals knowledge.” And as St. Paul writes in Romans, God’s “invisible attributes . . . his eternal power and divine nature” are “clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made.”

But it is unsurprising that I wrestle to find language to explain this incarnational principle as central to the holiness we experience in Tolkien’s writings. The Incarnation is Mystery—known and not known: known as far as our minds can grasp it, and unknown as we sojourn on, often unaware, until a glimpse of beauty catches our breath, something as small as the late winter snowdrop blooming in the lawn that we ought not to crush but instead venerate as another image of the character of God—“God,” who in the words of Martin Luther, “writes the gospel not in the Bible alone, but on trees and flowers, and clouds, and stars.”

In my attempt to explain Tolkien’s vision of incarnational reality, the phrase “participatory holiness” came to me. All of creation, we included, is called to participate in the holiness of God. Meaning, what?

God is a holy God, but we are not a holy people. While we are Imago Dei—made in the image of God—we also desacralize ourselves and each other through any number of sins, all of them deadly. For instance, in our time we witness increasing division in our world. Too often hostility has replaced the free exchange of ideas. A combination of fear and fury has led to a rapidly shrinking number of spaces for friendly dialogue. Defamation of an opponent’s moral character is common. Social media is frequently the platform where such division is fueled by the use of derogatory language. Fewer people, it seems, share the sentiment that “opposition is true friendship”—meaning that we can learn from one another, even be persuaded or remain unpersuaded by another’s perspective as the case may be, and all the while honour the other with sincere listening and respectful speech. Such dialogue is of course only possible among people of good will, people who refuse to dehumanize others because they regard the other as intrinsically valuable.

However, I’m happy to report that the other evening I had the great pleasure of hearing a scholarly presentation on a controversial topic followed by respondents with other perspectives. While the event, sadly, had been cancelled by one institution that I have always held in high regard (and still hope to in future), it did take place as planned, and unfolded just as it should have—in a humble spirit of true learning and kindly collegiality that I have been used to as the norm in earlier decades. Hallelujah—that such exchange is still possible in our angry world is a bright glimpse of goodness. All kudos to the organizers, the speakers, and the attendees. In response, I am both encouraged and admonished to go and do likewise: be a person of good will; strive to sincerely listen and speak respectfully; have courage and be kind; foster such spaces as far as it is in my power to do so. In my own small way, on a daily basis, may I consider how I am called to such participatory holiness in which I honour my fellow human being. Daunting? Yes. Perhaps the words of Mother Teresa help us here: “We can do no great things—only small things with great love.”

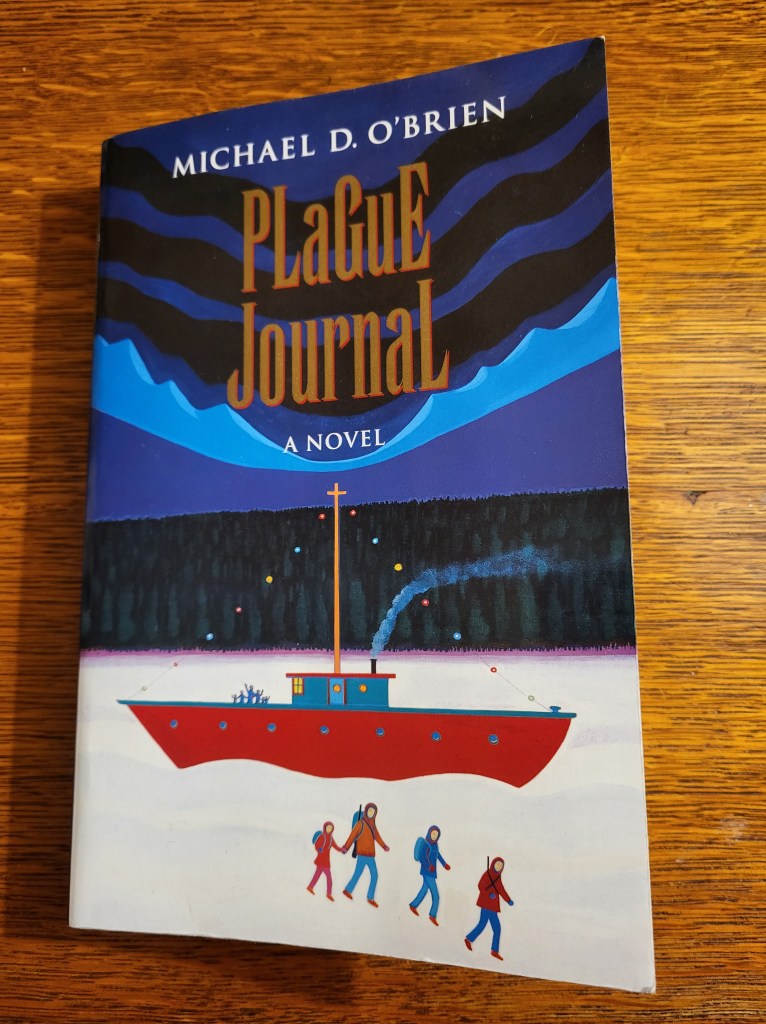

Recently I have been immersed in teaching Canadian author Michael D. O’Brien’s novel Plague Journal and it remains fascinating to me how the narrator speaks of every person as being a word from God, a living icon. The narrator, cradling his infant daughter in his arms, speaks of her as “a living icon, ‘a strong and delicious word’ never before seen, never to be repeated.” Earlier, struggling with this idea, he thought, “Maybe a word from God. Maybe this is the only liturgy I can handle right now.” Later, convinced of the reality of each person as a being made in the image of God, and therefore the body itself, including the corpse, as having sacred value, he challenges his friend’s detached response to the body of a murdered boy. When his friend shrugs off the value of honouring the body of the deceased, thinking that nothing matters, the narrator insists, “the body’s not just an old bag we slough off when we’ve finished with it. It’s holy, like a house full of love, or a shrine. It’s a home, and there’s nothing like it ever existed before or will ever be like it again. It’s a word spoken into the void. It pushes back the darkness by just . . . by just being.”

To think of a person as an icon is an astounding thought. “What is an icon?” I asked my students. After some searching, the word “picture” popped up. An icon is a picture, a special picture that helps one to pray. An icon is not an idol, I add. Rather, an icon is a sacred picture meant to open a window in our hearts and minds to the sacred. It is a living symbol—an interactive symbol. My own Lutheran faith tradition does not share the Orthodox one of iconography, but we do have art, including the gorgeous stained glass windows in the church that I grew up in. Here, parishioners paid to replace the plainer coloured glass windows with these brilliant windows depicting biblical scenes, and whenever I visit, gazing on these windows seems to have the effect of enlarging and softening my soul a little. Art can be a portal, a door or gateway to a larger experience of reality—to the sacred nature of reality. [Photo credit: Cyrus Heimann © 2017]

While we easily associate iconography with religious imagery, it is also embedded in computer technology, as my husband reminds me. With the emergence of Windows in the 1980s, we’ve been invited to click on a thumbnail image that will open the portal to a program, now referred to as an app (an application icon). The computer icon is a live thing—a hyperlink to the program we ask for. While we tend to divide the sacred from the so-called ordinary, and often think of technology as dehumanizing, perhaps our computer technology can also remind us of the deeper meaning of an icon—a portal, a hyperlink to the sacred, waiting for our response. After all, not one thing is outside of the incarnational nature of Creation. In Madeleine L’Engle’s words in Walking on Water, “There is nothing so secular that it cannot be sacred, and that is one of the deepest messages of the Incarnation.”

The mystery of the Incarnation. The incarnational principle of Creation. The sacramental nature of Creation. People as living icons, as unique words from God. These are all heady concepts, potent ideas beyond easy comprehension. Yet, they are as close to us as our next heartbeat, our next breath. Maybe the next snowdrop, maybe the next stranger’s face, will humble us into an openness to participatory holiness.

Since God is a holy God and we are not a holy people, this ongoing call to participatory holiness is a call to continual repentance. So we ask for mercy. As the line in the song goes, “Our sins they are many, His mercy is more!”

Thanks for reading, for listening.

You can order your copy of Letters to Annie at Amazon, FriesenPress, or through your local bookstore.

Sign up to receive my blogs at https://monikahilder.com/

Follow me on Social Media:

Watch for my Summer blog in June: “When I Grow Up”