It wasn’t supposed to happen like this—the panic, the flight, the last glimpses of our ancestral lands. Nor the trek through the woods at night with a few belongings, watching for enemy soldiers and other possibly unfriendly eyes, hiding, then walking again, walking, hiding, walking again, carrying the children, supporting the aged parents, our men fighting in a war they didn’t ask for, and praying, praying, hoping against despair, praying. Then riding the open flatbed rail car through the bombed-out landscape that was to become our new place, all the while swallowing the continually rising nausea over the knowledge that our homeland was no more—not for us. There could be no return. Once we had belonged; overnight we had become refugees. Once we had a past and a future; now we had a past . . . but what else? Once we had homes, livelihood, community. Overnight we had lost it all—and we were the lucky ones.

The above narration is a glimpse of what my people experienced at the end of World War II on their flight from Poland to war-ravaged Germany. For me, as the first Canadian-born in my family, I continue to ponder the meaning(s) of homeland, the plight of the refugee, and identity: in short, the importance of story. I suppose I’ve been gifted with “bifocal” vision whereby homeland means the origin country where my people had dwelt for generations as well as all the new homelands that my family and relatives had rerouted themselves to. I say “rerouted,” which slides off the tongue easily enough, as if they had used GPS coordinates. But the better word is “rerooted,” whereby you put your old roots down into new soil and, you hope, you pray, these roots, having been so abruptly pulled up, perhaps not too damaged, will find and be able to receive nourishment elsewhere, and so one day thrive again. For my own people, I can say the experiment succeeded. And in my native land that I love, Canada, I know that I am a pilgrim in a much larger story—a guest, in fact, on planet earth.  This would explain why the Canadian poet Al Purdy’s poem “A Handful of Earth” resonates with me. He writes,

This would explain why the Canadian poet Al Purdy’s poem “A Handful of Earth” resonates with me. He writes,

I wondered who owns this land

and knew that no one does

for we are tenants only. . . .

my place is here. . .

this place where I stand. . . .

only this handful of earth

for a time at least

I have no other place to go.

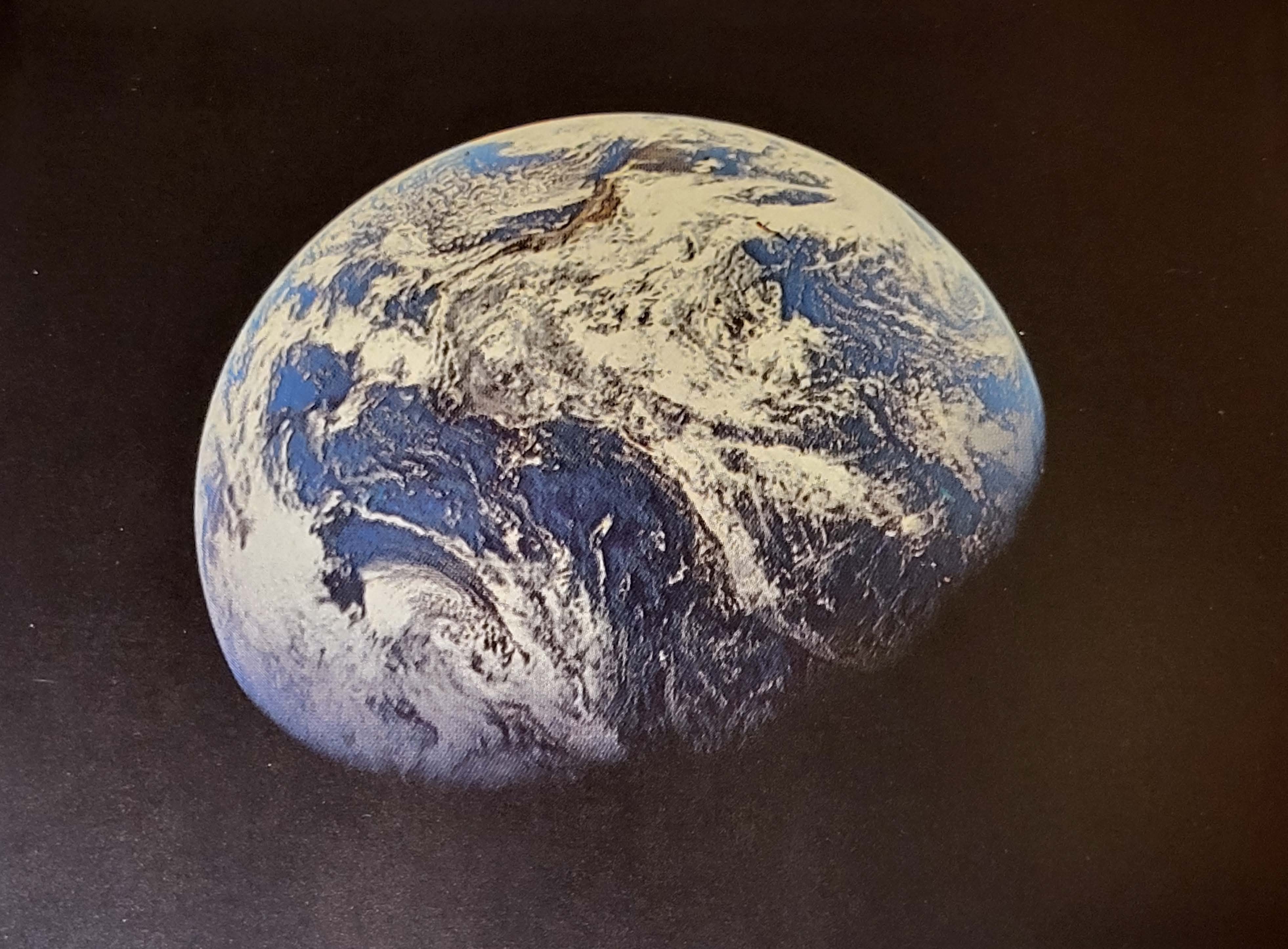

But as a conscious pilgrim, a tenant-guest, I wonder sometimes what it might feel like to belong to people who have lived in one location for centuries. If you are that person, I sometimes wish I were you. Yes, I typically marvel over people who have lived in one location in relative peace for generations, their ancestors before them, and now they with their extended family and friends. There must be something deeply satisfying, near magical, to be so rooted, so known. If you are that person, can you tell me if that is so? Satisfying, near magical? You hesitate to answer, perhaps? Did I hear you say, “No. It’s more complicated . . . more complicated by far—”? Of course, yes, I know that too: trauma history is not limited to experiences of war and flight. Might you agree then that we are all pilgrims? Guests on planet earth who can choose to live as faithful tenants on a handful of earth, or not? While we are so often divided, alas, we are nonetheless united, whether we like it or not, in pilgrimage on this beautiful and also aching, groaning, weeping planet. And so, if you like, let’s contemplate the story of another guest on planet earth.

It wasn’t supposed to happen like this—the untimely child, or so some thought. “Now? Like this?” What were his parents thinking? His coming, even before his eyes saw the light, united some and divided others. Oh, the terrors of that time. The innocent babies slain while his parents fled with him to a strange land, a place of safety, until it was time to return to his native land, not exactly a place of safety, not for him. And always his own people are assaulted, murdered, often most brutally, again and again and again. Do the nations not know they are to receive the ultimate blessing through his people: the ultimate gift, the Saviour of the world? Or is this the very reason that his people continue to suffer so grievously, because of those who despise the ultimate gift?

“He was a king, you say? That’s a bit much, don’t you think, even for delusional parents like his. They were refugees, right? What? What?! He was the Creator Himself–? This, this, this nobody? This, uh, what? Carpenter? Refugee? Let’s just say it: loser. Maybe a gentle soul, but a loser nonetheless. Oh sure, you say ‘he was born to die.’ Who isn’t? So tell me another one. But oh, uh, you’re serious. . . .”

It was, yes, supposed to happen like this. His coming, his dying. Once we had made the evil choice and lost our home, the one that introduced death and all our woe, his coming united some and divided others. It was supposed to happen like this. Then as now, those who receive Him receive life, for He is Life. Those who reject him do so to their own judgment. This expected and at once unexpected child—the Christ—born to die so that we might live: this child, the Christ, once came as a guest on planet earth.

Unthinkable: the Creator coming as a guest on the planet where we are only tenants, potential good stewards, or not. The unimaginable: yes, it was supposed to happen like this. Born to die; born to rise again—and as John Donne exclaimed, echoing St. Paul, because of the Supreme Guest, “Death, thou shalt die.” Yes, Messiah’s life for ours; His life, ours, forevermore. And so, we, lost to our original homeland, Eden, are guests on planet earth, tenants, gifted through Christ to journey on this pilgrimage to our true country, our Home, where all things shall be made new.

This Christmas season, I’m pondering the astounding idea of our Saviour first coming as a guest on planet earth. What wondrous mystery is this? That our Creator should be willing to come as a lowly visitor to his own planet, as a humble pilgrim born to suffer and to die a horrible death—all for love of us. Our Guest on planet earth, the Creator incognito, who came for me, came for you, so that we, mere pilgrims, might find our true forever Home.

Now, for however many days are allotted to us, on whatever handfuls of soil are given to us, may we steward them well. And one day, on that Great Day, when our earthly sojourn is over, may we hear our Saviour say, “Well done, thou good and faithful servant.”

Wishing each and all of you a truly joyous Christmas!

Thanks for reading, for listening.

You can order your copy of Letters to Annie at Amazon, FriesenPress, or through your local bookstore.

Sign up to receive my blogs at https://monikahilder.com/

Follow me on Social Media:

Watch for my spring blog in March: “And Daffadillies fill their cups with tears.”

Well said.

Sent from my iPhone

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLike

Thank you very much.

LikeLike