Are you ever tempted to read the last chapter of a book before you have even begun reading the first chapter? Or, if you’re somewhere in the middle of reading it, have you been tempted to skip ahead to the end to see if you really want to read the whole thing? Or maybe you shudder at the mere thought of “Spoiler!” and vigilantly resist such temptations?

I could be wrong, but I don’t think I’ve ever read ahead to the last chapter of a novel. But I know of someone dear who did, and the larger meaning of reading the ending early on has stuck with me. If the ending of a story is a good one, then no matter how hard and even terrible the journey is to get there, then the good ending makes it all worthwhile, doesn’t it? Of course, the ending would have to be very good indeed for this to be so.

In my epistolary novel Letters to Annie, when Annie is almost 25 and her Omi 89, I pondered my own beloved mother’s boast of reading the last chapter of novels this way:

“I always smile to recall my mother’s amused boast that she’d read the last chapter of a book in order to decide if it was worth reading. (Your great-grandmother Käte was indeed hilarious. Quite rascally at times. Endearingly so.) If she liked it, she’d read the entire book. If not, she congratulated herself on not having wasted her time on a disagreeable or inferior book. You’d think she was cheating herself of the experience of gradually arriving at the last chapter, but she didn’t see it that way. Time is precious, there are many good books to read, and she wanted the best. Normally I don’t recommend reading the last chapter first, but I will say this: while life is undoubtedly a journey, there is also a destination, as our Lord has clearly spelled out. And since we know that the last chapter of our lives leads to eternity and facing our Lord, how much differently might we then live?”

Today, on the cusp of change from the old year to the new, I’m wondering how we go about reading the Last Chapter of life, our lives. When the lights of Hanukkah and of Christmas are all too swiftly receding, what precious memories will you cherish? Has this past year been a good year for you? With what hopes and perhaps fears, dreams and possible anxieties, are you entering the new year? Which sorrows have marked your path? What are you taking with you on this next leg of the pilgrimage? And which destiny do you hope to arrive at? Do you think that this life is all there is, or, as believers across the generations have said, the best is yet to come? How do you read the Last Chapter?

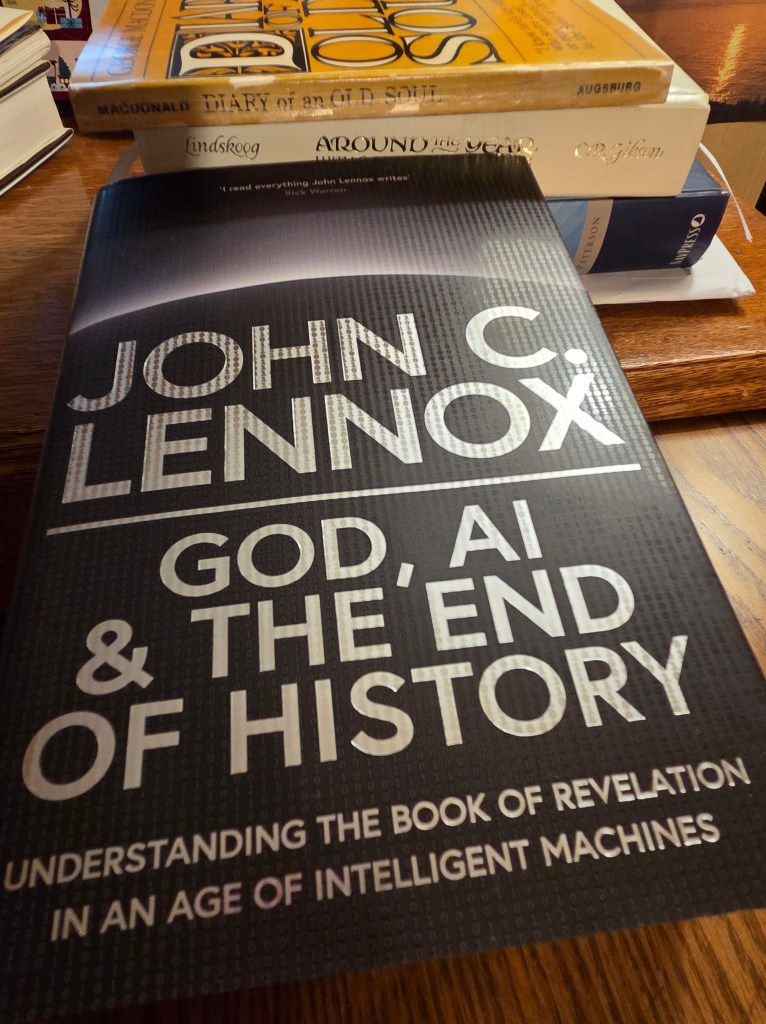

This season I’ve been enjoying reading John C. Lennox’s newly published book God, AI & The End of History: Understanding the book of Revelation in an age of intelligent machines. This is heavy-duty stuff alright, but good. Here, in the context of the devastating realities of our contemporary world, a shocking mix of climate change, economic misery, wars, and the advancement of artificial intelligence, Lennox thoughtfully and humbly speaks to the ultimate hope that we find described in this last book of the Bible, the book of Revelation: this book that we might be tempted to avoid, which would be to our peril, but if read prayerfully, soberly, with an open heart and mind, leads to profound blessing.

How we read the Last Chapter of life makes all the difference to how we live. And in our own ending, when death comes, is the ending silence, nothingness, meaninglessness—or is it a pause, almost imperceptible, before we take the next breath into eternity, into the very presence of God? If it is the first, well, then we might try to please ourselves with what we believe will please us while we can. But if it is the second, then we have some serious thinking and repenting to do. What are we living for? How can we cope with evil, suffering, and death? Is there ultimate hope? What has God to say to us about all these questions?

Consider how the composer George Frideric Handel told the full story of human history from the Bible in his oratorio about Christ, Messiah. I had the privilege of attending its performance in Vancouver’s Orpheum Theatre this Christmastide. We’d come through heavy traffic, observing some of the much human misery along the way, and arrived breathlessly, beating hearts, just in time. And truly, this side of eternity, there are perhaps few things as thrilling as joining the full house rising to their feet for the resounding “Hallelujah Chorus.” And at the conclusion of the oratorio, the standing ovation with ongoing whistling and cheering was astounding. Consider the concluding chorus to Handel’s Messiah:

“Worthy is the Lamb that was slain, and hath redeemed us to God by his blood, to receive power, and riches, and wisdom, and strength, and honour, and glory, and blessing.

Blessing and honour, glory, and power be unto him that sitteth upon the throne, and unto the Lamb, for ever and ever.

Amen.“

Thus, the short answer on the last chapter to the long story of human history is this: Joy. God wins. Yes and Amen.

So, on the cusp of this new year, and when the last festive lights will have faded, I’d like to encourage us to consider how we read the Last Chapter of life. How we read the Last Chapter makes all the difference on how we continue the journey.

And in conclusion, I’d like to point to another favourite last chapter: this one from C.S. Lewis’s The Last Battle. My guess is that Lewis wouldn’t have minded terribly much, or at all, if you, in case you’ve not yet read his Chronicles of Narnia before, pick up this final story and turn to read the last chapter, “Farewell to Shadowlands”—in the spirit of checking out whether or not this is the kind of story that you’d like to enter into. In this last chapter, after having come through the cataclysmic trauma which ended the world of Narnia that they loved, the children and all others find themselves in their real country where they realize that they cannot feel afraid even when they try. Instead, filled with wonder, they can run without getting tired and when they encounter the Great Waterfall they . . . well, I shouldn’t recount what happens then: you will need to read that for yourselves. But I don’t think Lewis would have minded if I repeat the final lines of this last chapter:

“And for us this is the end of all the stories, and we can most truly say that they all lived happily ever after. But for them it was only the beginning of the real story. All their life in this world and all their adventures in Narnia had only been the cover and the title page: now at last they were beginning Chapter One of the Great Story which no one on earth has read: which goes on for ever: in which every chapter is better than the one before.“

And so Lewis’s novel closes.

Thanks for reading, for listening.

You can order your copy of Letters to Annie at Amazon, FriesenPress, or through your local bookstore.

Sign up to receive my blogs at https://monikahilder.com/

Follow me on Social Media:

Watch for my March blog: “Seeing Things.”

This life can be so mind-boggling, so utterly overwhelming, that language fails. In a sense, language will always be inadequate to express what we deeply feel and surprisingly discover. But today I’ll try to form a few thoughts about this wildly beautiful and at once deeply disturbing life that we live: mind-bogglingly glorious and also intensely pain-filled.

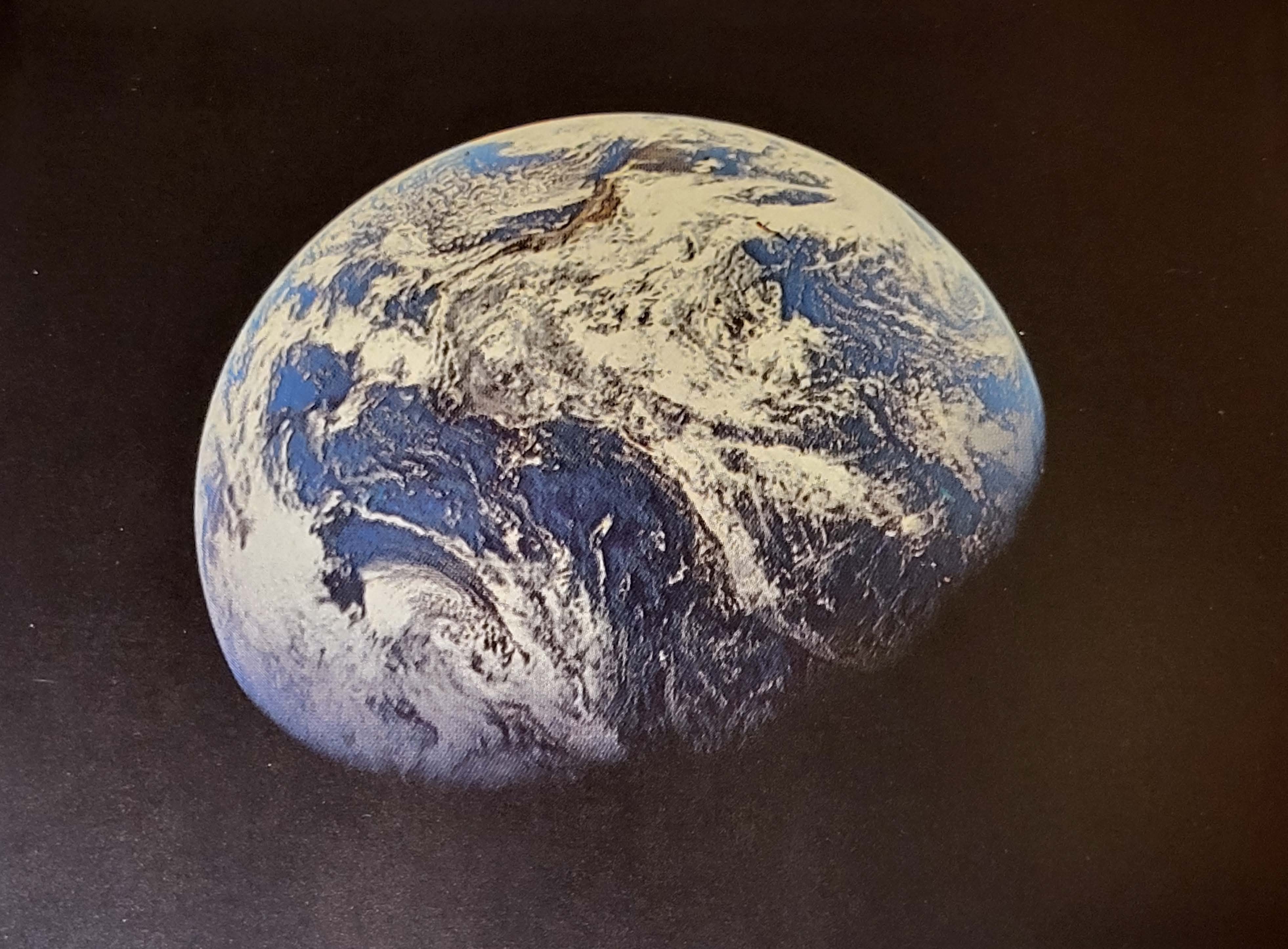

This life can be so mind-boggling, so utterly overwhelming, that language fails. In a sense, language will always be inadequate to express what we deeply feel and surprisingly discover. But today I’ll try to form a few thoughts about this wildly beautiful and at once deeply disturbing life that we live: mind-bogglingly glorious and also intensely pain-filled. This double image of family history is extraordinary to me, the double image of trauma and peace: the picture of my mother kneeling here, cleansing clothing in this very spot, and decades later me standing here with my husband as the water continues to flow. Quiet marvels in a long story. The wonder of it all is that we get to be alive on what Madeleine L’Engle has called this “

This double image of family history is extraordinary to me, the double image of trauma and peace: the picture of my mother kneeling here, cleansing clothing in this very spot, and decades later me standing here with my husband as the water continues to flow. Quiet marvels in a long story. The wonder of it all is that we get to be alive on what Madeleine L’Engle has called this “ When I pass around this rock to my university students, some gasp, “This is history! History!” and some ask, “What was the Berlin Wall?” It is amazing, is it not, that while many of us did not expect to see this wall gone in our lifetime, it went. Today I’m privileged to show this rock as an illustration that paradigms change. Just when we think some things are fixed, will continue indefinitely, they vanish. We ought to be careful, ought we not, as to how we navigate paradigms. The unbalancing through paradigm change, while often disturbing, can be healthy too. I’m reminded of walking on the unevenness of cobblestone paths.

When I pass around this rock to my university students, some gasp, “This is history! History!” and some ask, “What was the Berlin Wall?” It is amazing, is it not, that while many of us did not expect to see this wall gone in our lifetime, it went. Today I’m privileged to show this rock as an illustration that paradigms change. Just when we think some things are fixed, will continue indefinitely, they vanish. We ought to be careful, ought we not, as to how we navigate paradigms. The unbalancing through paradigm change, while often disturbing, can be healthy too. I’m reminded of walking on the unevenness of cobblestone paths. You’d be a fool to just march on as if you owned the road, as if the unaccustomed road would shape itself to your desires, as if the smoother pavement you’re used to walking on is everywhere. It isn’t. But wearing comfortable shoes while treading gingerly on old, cobbled paths helps in rebalancing. And in the rebalancing, it also awakens in me enchantment—the wonder that I am walking where people over the centuries have walked. I catch my breath, realizing anew that I have a small part in a long story. And this should give me great pause, to consider what their lives might have been like, to consider which paradigms they understood that have since shifted or even disappeared altogether, to listen to their words as best as I can. I’d be a fool to not care about what they can say to me.

You’d be a fool to just march on as if you owned the road, as if the unaccustomed road would shape itself to your desires, as if the smoother pavement you’re used to walking on is everywhere. It isn’t. But wearing comfortable shoes while treading gingerly on old, cobbled paths helps in rebalancing. And in the rebalancing, it also awakens in me enchantment—the wonder that I am walking where people over the centuries have walked. I catch my breath, realizing anew that I have a small part in a long story. And this should give me great pause, to consider what their lives might have been like, to consider which paradigms they understood that have since shifted or even disappeared altogether, to listen to their words as best as I can. I’d be a fool to not care about what they can say to me. A small image of the helium hope came to me along a walkway around McMillan Lake on my campus, an old swing from a willow tree beckoning still. Also the words of Psalm 24 on this same pathway begin thus: “The earth is the LORD’s, and everything in it, the world, and all who live in it. . . .” Stopping to reflect on such things steadies me some. A few other recent experiences point to ultimate Joy.

A small image of the helium hope came to me along a walkway around McMillan Lake on my campus, an old swing from a willow tree beckoning still. Also the words of Psalm 24 on this same pathway begin thus: “The earth is the LORD’s, and everything in it, the world, and all who live in it. . . .” Stopping to reflect on such things steadies me some. A few other recent experiences point to ultimate Joy.

If maturation hasn’t fully happened by now, when might it? I do like Walter Hooper’s hearty dismissal of the idea that C. S. Lewis’s attitudes toward women changed from early sexism to increasing egalitarianism, especially through his marriage to Joy Davidman in later life, which goes like this: as if Lewis “did not know what life was about until the age of fifty-eight.”

If maturation hasn’t fully happened by now, when might it? I do like Walter Hooper’s hearty dismissal of the idea that C. S. Lewis’s attitudes toward women changed from early sexism to increasing egalitarianism, especially through his marriage to Joy Davidman in later life, which goes like this: as if Lewis “did not know what life was about until the age of fifty-eight.” I recall that pivotal moment in the department store when my eyes first spotted the chair and I made a beeline for it, plunked down into it, and started rocking away, marveling at this chair that was just my size, perfect in every way, and smiling up at my parents in the firm belief that the chair was mine, mine, just waiting for me. I wasn’t getting up any time soon, not until it was clear that this chair was coming home with me. There was no doubt in my mind that this was my chair, though I kind of knew I was getting away with something when my confidence resulted in my loving parents smiling down at me and then buying the chair. (No, my insistence on things didn’t always work, thank goodness. . . .) This child-sized rocking chair is a sweet memento of the childlike wonder and joy that I long to keep alive always. I admit, I had to dust the chair off somewhat just now, something I should really do more often. Yes, the intention to fan the flame of childlike wonder over the decades is no easy feat. Joy is too easily displaced by the grime of unworthy thoughts.

I recall that pivotal moment in the department store when my eyes first spotted the chair and I made a beeline for it, plunked down into it, and started rocking away, marveling at this chair that was just my size, perfect in every way, and smiling up at my parents in the firm belief that the chair was mine, mine, just waiting for me. I wasn’t getting up any time soon, not until it was clear that this chair was coming home with me. There was no doubt in my mind that this was my chair, though I kind of knew I was getting away with something when my confidence resulted in my loving parents smiling down at me and then buying the chair. (No, my insistence on things didn’t always work, thank goodness. . . .) This child-sized rocking chair is a sweet memento of the childlike wonder and joy that I long to keep alive always. I admit, I had to dust the chair off somewhat just now, something I should really do more often. Yes, the intention to fan the flame of childlike wonder over the decades is no easy feat. Joy is too easily displaced by the grime of unworthy thoughts. (Yes, you might recognize this loose paraphrase from Lewis’s The Four Loves).

(Yes, you might recognize this loose paraphrase from Lewis’s The Four Loves). The statement raises important questions. Am I seeking affirmation from others when instead I need to give love? Can I love people more without requiring a return on the investment? The idea is tricky because it could easily slide into vanity, aloofness, but the intention is that as I become more secure in knowing that I am loved by God, I can deepen, heal, grow stronger. And out of that better place I can become more loving.

The statement raises important questions. Am I seeking affirmation from others when instead I need to give love? Can I love people more without requiring a return on the investment? The idea is tricky because it could easily slide into vanity, aloofness, but the intention is that as I become more secure in knowing that I am loved by God, I can deepen, heal, grow stronger. And out of that better place I can become more loving.

It’s my privilege and my pleasure to teach some of my favorite authors like J.R.R. Tolkien to university students. More often than not they come to me as ardent Tolkien fans. Sometimes they wonder, “Was he sexist? Maybe racist?” and such questions make for much needed discussion. (Essentially, my position on these two important questions is “No. No.”) But not once have I met a student who doubted the author’s love of nature: of trees, trees, and of all green growing things. This celebration of the natural world, together with the indomitable courage of hobbits, elves, dwarves, and wizards against the forces of darkness, inspires hope. Middle-earth is worth fighting for. There’s something sacred at stake here.

It’s my privilege and my pleasure to teach some of my favorite authors like J.R.R. Tolkien to university students. More often than not they come to me as ardent Tolkien fans. Sometimes they wonder, “Was he sexist? Maybe racist?” and such questions make for much needed discussion. (Essentially, my position on these two important questions is “No. No.”) But not once have I met a student who doubted the author’s love of nature: of trees, trees, and of all green growing things. This celebration of the natural world, together with the indomitable courage of hobbits, elves, dwarves, and wizards against the forces of darkness, inspires hope. Middle-earth is worth fighting for. There’s something sacred at stake here.

The phrase, “And Daffadillies fill their cups with tears,” from John Milton’s elegy “Lycidas” lingers in my mind as only a sorrowing beauty-filled thought can. Daffadillies, daffadillies—what lovely sounds to have roll off the tongue. Such beauty, and yet, yes, with such beauty, tears. Whole cups of tears, tears to overflowing.

The phrase, “And Daffadillies fill their cups with tears,” from John Milton’s elegy “Lycidas” lingers in my mind as only a sorrowing beauty-filled thought can. Daffadillies, daffadillies—what lovely sounds to have roll off the tongue. Such beauty, and yet, yes, with such beauty, tears. Whole cups of tears, tears to overflowing.

“Weep no more . . . weep no more,

“Weep no more . . . weep no more,

This would explain why the Canadian poet Al Purdy’s poem “A Handful of Earth” resonates with me. He writes,

This would explain why the Canadian poet Al Purdy’s poem “A Handful of Earth” resonates with me. He writes,

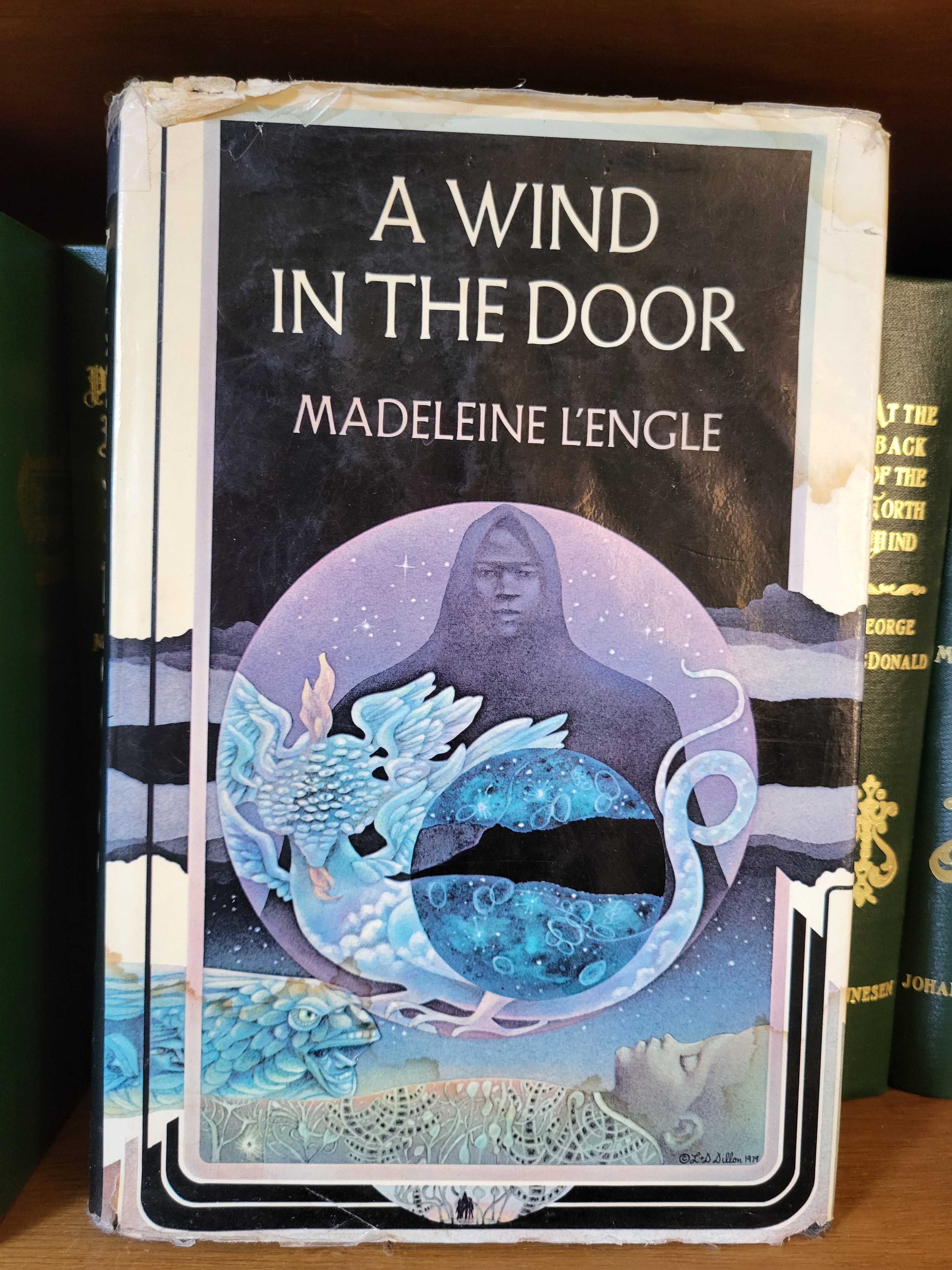

Then he adds with a laugh, “My dears, you must not take yourselves so seriously. Why should school be easy for Charles Wallace?” Taken out of the context of the story, Blajeny’s response might seem uncaring, even cold, and possibly dangerous. But it’s clear in the story that this is not the case. The fact is that Blajeny cannot make Charles Wallace’s problem disappear. There is no magic wand. But Charles Wallace is learning to adapt and defend himself, and the once ineffective school principal Mr. Jenkins grows in moral character to the point where he looks forward to dealing with the problems in his schoolhouse. Unlike Meg’s small view of what this Teacher’s purpose is, Blajeny has arrived for the far greater reason of guiding his students into discovering the nature of their battle against evil, and therefore for strengthening their readiness to meet it.

Then he adds with a laugh, “My dears, you must not take yourselves so seriously. Why should school be easy for Charles Wallace?” Taken out of the context of the story, Blajeny’s response might seem uncaring, even cold, and possibly dangerous. But it’s clear in the story that this is not the case. The fact is that Blajeny cannot make Charles Wallace’s problem disappear. There is no magic wand. But Charles Wallace is learning to adapt and defend himself, and the once ineffective school principal Mr. Jenkins grows in moral character to the point where he looks forward to dealing with the problems in his schoolhouse. Unlike Meg’s small view of what this Teacher’s purpose is, Blajeny has arrived for the far greater reason of guiding his students into discovering the nature of their battle against evil, and therefore for strengthening their readiness to meet it. Now that school or college and university has begun for many of us, I am left pondering Blajeny’s core challenge again: “Why should school be easy?” If I vote for “easy,” what am I looking for and, if I got it, would that be good? If I vote for “hard,” what should that be and why might that be better? Obviously, these questions can take us in several directions—the topic is that important. But for today I’d like to focus on Blajeny’s challenge: school should not be easy.

Now that school or college and university has begun for many of us, I am left pondering Blajeny’s core challenge again: “Why should school be easy?” If I vote for “easy,” what am I looking for and, if I got it, would that be good? If I vote for “hard,” what should that be and why might that be better? Obviously, these questions can take us in several directions—the topic is that important. But for today I’d like to focus on Blajeny’s challenge: school should not be easy. In his essay “Learning in War-time,” C. S. Lewis compares the educated person to the well-travelled one. He writes, “A man who has lived in many places is not likely to be deceived by the local errors of his native village: the scholar has lived in many times and is therefore in some degree immune from the great cataract of nonsense that pours from the press and the microphone of his own age.” Lewis, like others, was worried about the outcome of modern education based on moral relativism. Unlike the old idea of education founded on objective moral truth which is the basis for our freedom and intrinsic human worth, summed up nicely in the phrase “Veritas, Libertas, Humanitas”— Latin for “Truth, Liberty, Humanity”—a modern idea of education founded on moral relativism is the soil for enslavement and dehumanization. Lewis argues that moral relativism not only leads to inferior learning but opens the door to elite controllers who will work to reshape the masses to conform, and so enslave, to the agenda of their era. (See his book

In his essay “Learning in War-time,” C. S. Lewis compares the educated person to the well-travelled one. He writes, “A man who has lived in many places is not likely to be deceived by the local errors of his native village: the scholar has lived in many times and is therefore in some degree immune from the great cataract of nonsense that pours from the press and the microphone of his own age.” Lewis, like others, was worried about the outcome of modern education based on moral relativism. Unlike the old idea of education founded on objective moral truth which is the basis for our freedom and intrinsic human worth, summed up nicely in the phrase “Veritas, Libertas, Humanitas”— Latin for “Truth, Liberty, Humanity”—a modern idea of education founded on moral relativism is the soil for enslavement and dehumanization. Lewis argues that moral relativism not only leads to inferior learning but opens the door to elite controllers who will work to reshape the masses to conform, and so enslave, to the agenda of their era. (See his book  .) Does this sound like an overly harsh judgment on much of modern education? Maybe, or maybe not?

.) Does this sound like an overly harsh judgment on much of modern education? Maybe, or maybe not?